Home is always a ship

Book-length essay consisting of text, photographs, scans, documents and ephemera.

Excerpted in Failed States (2019)

Planes take off and land, people go to church or mosque or temple, to their jobs in the airport during the week, international flight crews flow in and out on overnight stopovers, the jumble sale takes place every month, protests take place every year, flowers are laid on memorials, bulbs are planted on the village green then removed a few months later, men are delivered or taken away in shackles in the early hours of the morning, some kill themselves, landladies retire and move away, tourists spread out from the coach, the old barn has its open day. Trees flower and lose their leaves or (being non-deciduous) grow steadily, recording how the environment changed from year to year with their billowing forms and shapes, the rings in their trunks. Lawns are mowed, crops are harvested, notes are made. Fields sink.

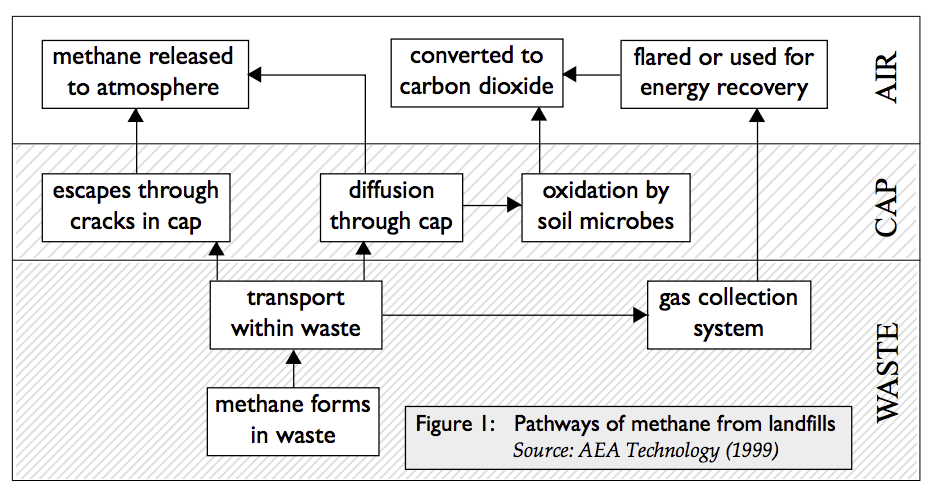

Fields sink because gravel is mined from what used to be agricultural land, then rubbish is put into the ground in its place, and then fields are laid back on top. Pipes stick out of the ground near footpaths and fences, vents for the gases released by the rubbish as it decomposes underground. Fields over landfill gently sink for years after they are laid, settling over the contours of their new archeology.

*

“Home is always a ship,” says the sailor Gerard Gales in B. Traven’s The Death Ship (1926). Gales loses his identification documents in the first pages of the novel and spends the rest of it drifting around the world, from border to hostile border, ship to leaky ship. Sailors, according to Gales, “don’t even know which company the ship they are on belongs to.” Their only interest is the ship that is their home and that nourishes them.

It’s hard to imagine an air steward talking about a passenger jet in such terms. For air crew it’s the opposite of what Gales describes — the company that you belong to is what gives the work its peculiar character, while the vessels themselves shuffle across the globe anonymously, internationally, their crews chopping and changing day by day, hour by hour. Air crew hardly have a chance to get acquainted with each other during a voyage, unlike the sailors on the ‘Yorikke’ — Traven’s eponymous death ship — and some staff rotas are designed so that you would have to toil for about six years, on average, before you worked onboard a flight with same person twice.

It was Stan who told me this latter fact, during one of the first interviews I did in Harmondsworth, recorded on my phone in Costa Coffee in a hotel next to the perimeter wall of the airport, set back from the Bath Road, behind the McDonalds, not far from the detention centre. Stan, now retired, is part of curious demographic in this area that has been created by the airport, since it was built on land requisitioned by the government under war laws in 1945.

Stan reads The Daily Mail, votes Tory, goes to church (he is the local churchwarden) and has been to more countries than you or I ever have or will. He knows the best places for sushi in Tokyo, has killed time strolling the streets of San Francisco and Singapore, and partied in Australia. (Unlike the brisk direct flight managed by some airlines today, the journey to Australia, in the seventies, used to be a twenty-one day peripatetic amble across the world, with multiple stopovers on the way and a carnivalesque sense of occasion — or so I gather from the misty look in Stan’s eyes as he describes it to me.)

People belonging to this uniquely late twentieth-century demographic can be found everywhere around Harmondsworth — like Penny, who worked on the luggage desk at Heathrow in the same era as Stan, and — like Stan — lives directly in the area that will be razed to the ground if the new runway is built. During the seventies, Penny once told me, she used to hitch a free ride on the plane to Los Angeles every single month to get her hair done at her favourite Hollywood salon. Her and Stan’s generation was given homes, stable incomes and pensions by the new age of global mobility that made the airport swollen and prosperous — until now, when these same homes are threatened by the airport’s continued rampant expansion, and the pollutants it pumps out into the area.

Then there’s another demographic in Harmondsworth, the kind of photographic negative to Stan and Penny, their counterweight. It numbers roughly a thousand, almost all men, but sometimes women and children. Most only stay in the area for a matter of weeks, but some have been stuck here for years.

*

It was in 1958 that air travel decisively began to supersede shipping as a mode of international passenger transport — that year, for the first time, more people travelled across the Atlantic by plane rather than by boat. Over the next decade new commercial jet routes began to spring up around the globe. By 1968 flights to and from Heathrow connected the U.K. to many of the countries which, up until very recently, had been its colonial possessions; countries like India, Sri Lanka, Nigeria, Jamaica, nations still known today — somewhat euphemistically considering the unidirectional flow of wealth that was colonialism’s defining feature — as ‘the Commonwealth’.

That year, fears about new arrivals from these countries prompted a landmark piece of anti-immigration legislation put forward by Labour: the Commonwealth Immigrants Act, which removed the right of entry to the U.K. for Commonwealth citizens and imposed onerous new restrictions, forms and queues. It was during the lead-up to this bill being passed that Enoch Powell made his ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech. Harmondsworth detention centre opened in 1970 to house the new victims of this legislation.

Legislation conjured the detention centre into being, and gathered people from all around the world inside it. Over the decades, legislation also expanded it and changed its purpose — by the late eighties Thatcher’s Conservative government had introduced stiff financial penalties for airlines if they allowed someone onboard without a valid visa. As a result the border was thrown outside of the U.K. into every point of departure around the world, and airlines were made into border guards. (The recent drownings in the Mediterranean are a direct result of this legal innovation, adopted by wealthier nations from the eighties onwards). The border was also drawn inwards, with an expanding immigration detention and border force bureaucracy. Police, doctors, landlords, bank clerks and university administrators joined airline staff in the effort to enforce the border.

These changes meant that Harmondsworth became less of a place to hold new arrivals from Heathrow until their papers were sorted, and more a place to detain those without visas picked up anywhere around the U.K. — a conduit for deportation flights out of Heathrow. By the turn of the twenty-first century it was the largest detention centre in the U.K., and in Europe.

*

In the late fifties, Hannah Arendt described the situation of the millions who found themselves stateless across Europe after the First World War. “The stateless person, without right to residence and without the right to work, had of course constantly to transgress the law,” she wrote. “He was liable to jail sentences without ever committing a crime.”

This was the nightmare, skilfully made tragicomic, that B. Traven’s stateless narrator faces in The Death Ship. “If you don’t belong to a country in these times,” he tells the reader, “you had better jump into the sea.” In every country he enters he is subject to officious, entitled interrogation — every police force has the authority (and inexplicable desire) to deprive him of his liberty; but none of them can give him a new passport. “I would give a second tenth of my million to find out who it is, in reality, that makes the laws about passports and immigration. I have not so far found an ordinary human being who would say anything in favour of that kind of messing up of people’s private affairs.”

*

She tries another tack. ‘Can you explain to me what exactly inspired you about Brian Cox?’

Amir once sent me his asylum interview, which he’s given me permission to reproduce here. The surreal questions repeatedly fired at him might have been funny, he told me, had the consequences of answering them incorrectly not been so serious.

He spent 52 days in Harmondsworth Immigration Removal Centre trying to secure his refugee status, without the help of a lawyer. Much of his case hinged around proving that, as a known atheist, it was unsafe for him to return to the country where he was born (where atheism is punishable by death). Hence the strangely urgent questions from the Home Office interviewer regarding the popular TV physicist Professor Brian Cox, whose factual science programming about the origins of the universe informed Amir’s nascent atheism in the eight years he lived in the U.K., before he was arrested at dawn by immigration officials and police, and taken to Harmondsworth.

*

Why am I telling you all of this? Because it is, in my opinion, the stuff you need to have in mind when you look at this collection of images, scans, documents and fragments. There are no portraits, but they are about people — the traces they leave and the structures they build; and all the different layers, levels, scales, experiences and degrees of displacement, piled on top of each other, exerting pressure on them, in this one small area west of London, sandwiched between an airport and a motorway.